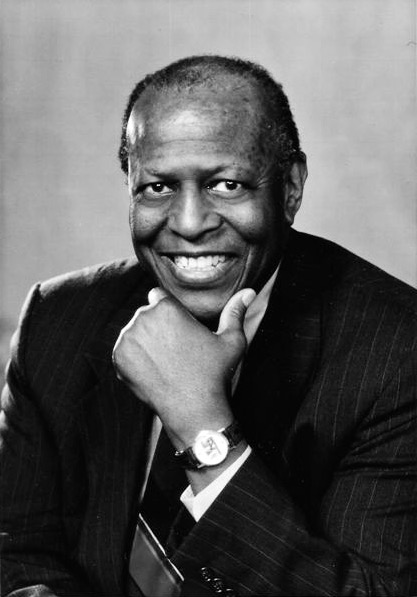

RIP: Charles V. Willie, first African American House of Deputies vice president, dies at 94Posted Jan 14, 2022 |

|

[Episcopal News Service] Charles Vert Willie, a sociologist and desegregation leader who served as the first African American vice president of The Episcopal Church House of Deputies and preached the sermon at the ordination of the Philadelphia Eleven, died Jan. 11 at age 94.

House of Deputies President the Rev. Gay Clark Jennings remembered Willie as “a giant in The Episcopal Church’s long and incomplete journey toward justice,” in a statement posted on the House of Deputies’ website on Jan. 14.

Willie, was elected vice president of the House of Deputies in 1970. He preached the sermon at the 1974 ordination of the first female priests at the Church of the Advocate in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Although Willie anticipated becoming the first Black president of the House of Deputies, he resigned as vice-president of the House of Deputies in the wake of the furor over the ordination of women.

“I have often thought that someone should write a ‘Profile in Courage’ of Episcopalians, and if they did, Dr. Charles Willie would surely be among those identified for profiles,” Presiding Bishop Michael Curry said in a statement to Episcopal News Service. “He gave up the chance to become president of the House of Deputies, and he did so following the dictates of his God-inspired, Gospel-shaped conscience. He chose not to play Pontius Pilate and instead chose the way of Jesus – the way of God’s love, compassion, and justice. For that he is a profile in courage.”

Current House of Deputies Vice President Byron Rushing remembered Willie’s commitment to intersectional justice, making advancements for both Black people and women in the church.

“Black Episcopalians were both proud of Chuck being elected first African American to Executive Council … and vice president of the [House of Deputies]. You can not overemphasize how racially segregated The Episcopal Church was before the ‘70s,” Rushing told ENS.

In a 1976 statement explaining his decision to resign, Willie wrote that he “could not act like Pilate and do what I knew was wrong.”

“I could not segregate, alienate and discriminate against women because it was legal to do this, and claim to be acting in love,” he wrote. “When that which is legal and that which is loving are in contention with each other, legality must give way to love. If The Episcopal Church would not change its sexist ways, I had to resign as an officer of the church for I could no longer enforce procedures which I knew were evil and sinful.”

In 2015, during its triennial meeting in Salt Lake City, Utah, General Convention adopted a resolution expressing its appreciation for Willie and he was honored on the floor in the House of Deputies.

“I presented Dr. Willie with the House of Deputies Medal for his distinguished service to the church at the 78th General Convention in Salt Lake City, and the house responded with a standing ovation that was much deserved and too-long delayed,” Jennings recalled in her statement. “He will not be forgotten.”

In the tenth anniversary issue of Ms. Magazine (August 1982), the editors celebrated Willie as a “male hero” for his contribution to the recognition of female priests in The Episcopal Church.

In a 2015 interview with Rushing, Willie recalled, “I decided I didn’t want to tell my children that I was the first African American to become [vice president of the House of Deputies] particularly when I know they won’t do well for women. … Some of my friends called me an angry Black man. They called me all kinds of things, but it never stopped me.”

Rushing told ENS that Willie’s resignation “had a profound effect on the bishops — which they have never admitted or confessed — and added to the success of the affirmative votes of both Houses in 1976″ for women’s ordination.

An obituary provided by Willie’s family and edited by Episcopal News Service follows:

Willie was most recently a resident of Boston, Massachusetts, after relocating from Concord, Massachusetts, where he had lived for 44 years.

Born at home in Dallas, Texas, on Oct. 8, 1927, Willie, a grandson of enslaved people, was the third child of five to Louis James Willie and Carrie (Sykes) Willie. Willie earned a B.A. in 1948 from Morehouse College, where he was elected class president. His class included young men who would become extraordinary leaders, including fellow sociology major Martin Luther King Jr. After earning a master’s degree at Atlanta University in 1949, Willie was awarded a doctorate in sociology in 1957 from Syracuse University’s Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs.

Willie taught at Syracuse University from 1950 to 1974, rising from graduate student lecturer to chair

of the Sociology Department and eventually vice president for student affairs. He was Syracuse’s

first Black tenured faculty member. Willie took a leave of absence from Syracuse at the invitation

of Robert F. Kennedy to direct the research arm of Washington Action for Youth, a crime

prevention and youth intervention program sponsored by President John F. Kennedy’s

Committee on Juvenile Delinquency and Youth Crime.

Willie returned to Syracuse in the mid-1960s, during which time he brought Martin Luther King Jr. to

speak twice at the University. In 1966-67, Willie took another leave from Syracuse at the invitation of

Harvard Medical School, where he taught and conducted research in its Department of Psychiatry as

part of the Laboratory of Community Psychiatry, and at Episcopal Divinity School. In 1974, Willie

left Syracuse to accept a tenured position as professor of education and urban studies at Harvard

University’s Graduate School of Education.

When Willie and his family moved to Massachusetts in the early 1970s, Boston was wracked by

tension and violence over white residents’ resistance to school desegregation. The judge overseeing

the case asked Willie to serve as one of four court-appointed masters to bring Boston’s landmark school desegregation case to a just conclusion. Several years later, Boston Mayor Raymond Flynn, a former student of Willie, invited him to develop a desegregation plan for the city. The plan, which Willie co-created with Michael Alves, became known as “Controlled Choice” and was used in Boston and Cambridge for decades.

President Jimmy Carter appointed Willie to the President’s Commission on Mental Health. An applied sociologist, Willie not only taught and conducted research but also applied what he learned in his work with others. He strove to bring the ideals of justice, equity, empathy, and reconciliation to every conflict he faced. He uncovered the best in everyone, understanding that no matter how intransigent the conflict, resolution required neither the annihilation nor the humiliation of opposing sides. Following those principles allowed Willie to build strong professional and personal bonds; he leaves behind a broad and diverse community of those who were touched by his grace.

He is survived by his wife of 59 years, Mary Sue (Conklin) Willie, daughter Sarah Willie-LeBreton, son Martin Willie, son James Willie and a large and loving extended family. Willie will be interred at Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Concord in a private burial service. A spring memorial service is planned. In lieu of flowers, donations may be made in Charles V. Willie’s name to Good Shepherd Community Care Hospice, the hospice organization of your choice or the Fellowship of Reconciliation.

Social Menu